Many people are looking for their passion – or have given up for lack of results. However, even for top performers their passion was seldom ‘love at first sight’, but grew throughout the years. So it may be better to learn how to nurture and grow an interest into a passion, than to hope that a perfect passion will just appear before your eyes one day. This post describes how one could get started on growing one’s passion.

Barring the few people who excitedly jump out of bed every morning, most of us probably wish that we had a bit more passion in our lives. Which is understandable, as having fun is, well… fun, and even from a scientific talent perspective, loving an activity or subject is useful, as it will increase the speed of learning about it, as well as the probability that you will get creative ideas about it.

The question for most people, however, is how to discover that passion. For a part, it may help to simply spend more time exploring new activities. For example, the psychologist Richard Wiseman states in his book “The Luck Factor” that lucky/’lucky’ people maximize their chance opportunities by trying out different hobbies, going to different places, and so on. However, more intense exploration cannot be the entire answer. After all, developing a passion for anything is like falling in love: while it can occasionally happen fast (‘on first sight’), that is no guarantee that it will last on the second or third sight. True passion for a subject or activity, like true love, probably needs to be developed over time to be more than a fun fling.

But how to do so?

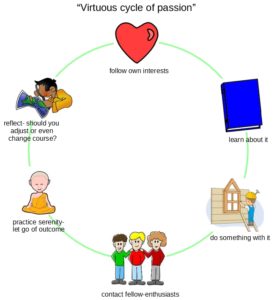

A while ago, I gave a workshop in Rotterdam, “Developing your inner Einstein”, in which I proposed a five-step process that many top scientists seemed to have followed, whether consciously or unconsciously. It involved following their own interests, learning more about their preferred subject, doing something with their knowledge, befriending fellow enthusiasts, and, at least to some extent, letting go of the outcome. Seems simple? Well, I listed some ‘gotcha’s’ below, as well as a sixth step, that may be useful for most people.

Step 1:

Select an activity that you like most (or dislike least) of your current activities. Note that there are two additional requirements:

-it must be something you yourself want to do, independent of what other people may want, like or push you to do.

-it must be something that you feel at least a bit proud of when you have done it; for example, if you are like most people, an activity like “watching television” may not fill you with pride – so don’t make it a “passion candidate”

Tip: if you find it hard to decide what interests you, take a tip from Isaac Newton and keep a ‘philosophical notebook’ in which, for say 5 minutes a day, you write down what interests/interested you today and what you would be interested in knowing more about in the future.

Step 2:

Learn more about the subject, whether by reading, talking with others, watching Youtube videos, listening to podcasts, going to lectures, or whatever method you like. Again, there are two important rules:

-don’t overdo it. Don’t be in a hurry; stop the learning/listening when you still want to learn more. As time goes by, you can ‘up’ the daily or weekly study time.

-Especially at first, choose learning methods that you enjoy and/or those created by people you admire, even if they are not the ‘best’ or ‘most efficient’ learning methods. Learning should always be fun, and it should especially be so in the beginning!

An example of a scientist following this rule was the physics Nobel laureate Richard Feynman, who as a first-year student decided to follow 3rd year physics courses, which he found more fun and challenging.

Step 3:

Do something with your interest. For example, if woodworking is your chosen ‘budding’ passion, you can try to execute a few designs yourself. If such a direct production is not possible, you can for example write about it (in a journal or blog), or make drawings, or give speeches or do something else, as long as it is somewhat related to the subject. Whether you communicate about the subject and/or experiment with it may not matter too much, especially not in the beginning. Again, the golden rule: keep it fun (don’t do ‘too much’, and first select activities on ‘fun’, not on ‘efficiency’/’usefulness’).

An example of this rule would have been the young Charles Darwin going out into the woods to catch beetles for his collection. Darwin loved bug-collecting so much, that once when he had a beetle in each hand and saw another beautiful beetle, he popped one of his hand-held beetles into his mouth for ‘safe keeping’ to grab the third. (He also learned from the experience that some beetles can bite).

Step 4:

Make friends! Seek out friends and clubs and websites and blogs and forums and whatever of people with similar interests! If those really do not exist, try to find something somewhat related with a larger community. For example, since the psychology of science is yet a very small community, I also try to keep track of people studying education, or arts and sports performance. Again, don’t overdo it, and keep it fun. The enthusiasm of others will keep you going even when the going is tough.

This was, by the way, also one of the ways in which the chemist Svante Arrhenius survived the disdain he received from his professors about his ‘silly’ theory that salts in solution split into so-called “ions”. The old professors did not believe him, but his young colleagues Wilhelm Ostwald and Jacobus van ‘t Hoff believed him and encouraged him. It was a pretty good ‘club’: Arrhenius’ ‘silly theory’ is now taught in every introductory chemistry book, and each of the three won his own Nobel prize.

Step 5:

Practice serenity: one of the most problematic aspects of passion is that many people want to earn their bread with it (or at the very least become famous with it). This is occasionally possible, but it is usually very hard, and requires mixing the activity you are passionate about with things you like less, whether that is administration or contacting potential customers. Even Einstein said:

Science is a wonderful thing if one does not have to earn one’s living at it. (…) Only when we do not have to be accountable to anybody can we find joy in scientific endeavor.

(Reply to a 24 Mar 1951 letter from a student uncertain whether to pursue astronomy, while not outstanding in mathematics).

Of course, if another profession offers more opportunities to follow your passion than your current profession does, feel free to pursue it! But regard ‘marrying’ a passion to a profession like a wise person regards marriage: while overall you may like the relationship, there will be stormy seas and disappointments.

Step 6: (or, perhaps, ‘component 6’)

Keep track of problems and opportunities. Reflect on what you do and what you experience. There are many things that can go wrong. For example, you can become too goal-driven (overstrain), which takes the fun out of the activity itself and can cause stress due to forcing you to give up too many other things you care about. ‘Dutyizing’ or staleness, where things become routine or automatic, and you lose the connection to the joy. You can become lonely or discouraged (if you don’t find people who encourage or support you), you can get too dispersed (undertaking too many activities and spending too little time on a single one to make yourself grow in skill and motivation, abandoning things prematurely). Also, sometimes a road leads naturally in a direction that does not really interest you, and you need to change course. It can help to regularly ask yourself questions like “How much fun is this?” “Which problems do I encounter?” “What opportunities do I see?” “How can I get in touch with others with the same interests?”

Finally, you may find that while practicing a passion, that you automatically drift to an adjacent field. Let it happen: the most important thing is that you enjoy what you are doing, and even the greatest of scientists switched fields occasionally.

In a picture (with apologies to the authors of the sub-pictures, whose credits I had not written down)

But… does it work?

This 6-step plan may look a bit naive at first sight, and it is, at least in the sense that, like a plant, passion needs to be provided with sufficient “water”. And the ‘water’ for passion is attention. If you are so poor that you have to work 17 hours a day just to survive, you won’t have time (or energy) to develop a passion. Whatever your passion is (like photography), if you can only spend 2 seconds a day on it, it can probably never flourish to a ‘proper’ passion, just like dating a person for on average 2 minutes a week will usually not be enough to develop a solid relationship. There probably are people who are so poor that they cannot and (unless they have a huge stroke of luck) will never be able to develop a passion.

On the other hand, one should also beware of being ‘too greedy’ or ‘a martyr’. Most people in western countries do not need to work 17 hours a day to be able to pay for enough food and possibly a place to sleep. Much of the money we earn goes to things that are nice to have (or with which to make the neighbours envious), but which don’t give us true joy or pride; much of our time is spent on either maintaining our set of possessions in an ‘acceptable’ state, or in maintaining our social relationships. Again: in most cases at least some of our relationships can survive with a little bit less attention, and our floor can stand to be vacuumed a little bit less frequently. In my opinion, having something that you like and care about is more important than having as many friends as possible; at the very least there should be a kind of balance between ‘passion time’, ‘social time’ and ‘maintenance time’. If you really can’t spend 15 minutes or even 30 minutes a day (or say 2 hours total per week) on something you deeply care about, you should probably try to change things in your life, like reducing contacts with your friends a bit, wearing the same clothes for more days, spending less money or (when work times are excessive) even quitting your job when you have enough to survive say 1 year of job-searching.

But even that may be more radical than needed: if you find that even in your limited amount of time you can develop an interest in/enthusiasm for something, you are very likely to find that you will automatically care less about feverishly following Facebook or cleaning your house or earning as much money as possible, as doing something you are genuinely proud of will go a long way towards reducing your need for social validation and the rather time-consuming pursuit thereof.

My personal experiences

You may wonder whether I am ‘taking my own medicine’. The answer (on July 2017) is ‘partially’. Like I guess most people, things go well for my interests if I obey one or more rules: when I was in highschool, chemistry was one subject of the many I encountered but which ‘stuck out’ a bit (principle 1), made me read a lot about it for fun in well-written books that I found (principle 2), prompting me to do things like making my own lists of elements and their properties and building molecular models (principle 3), and receiving social support, mainly from my father (who also liked science), though my chemistry teacher gave me at least a second role model (principle 4). I achieved ‘serenity’ basically by trusting that things would work out (point 5). However, the lack of reflection (point 6) made me neglect to try change things when at university, I found much of chemistry boring (experiments or mathematical derivations), did not encounter role models or clear encouragement. Had I more aggressively sought out my own reading lists or projects in my spare time, I would likely still not have pursued an academic career, but I would definitely have had more fun while studying and not have had my ‘end-of-PhD-gap’ in which I did not know what to do. I’ve now taken on a small ‘passion project’ (developing a tool in JavaFX to help me manage my scientific talent notes), and, while 10 years may be a tad too long for a report, I’ll link an update to it in 3 months.

Conclusion

Provocatively, I would say that unless you are extemely poor, if your life seems void of passion, you don’t lack luck, you lack skill – passion-growing skill, that is.

Longer version: it’s great if you can discover your passion, but it is definitely also useful if you can develop a passion if none seems to pop up spontaneously. If you follow the steps of listening to your heart, learning, doing, befriending, ‘letting go’, and reflecting, even if you do it only a little bit or rather clumsily at first, you will be able to grow even the tiniest seed of passion into a flourishing flower that nurtures your spirit and the rest of your life.

May you bloom happily!