There are lots of books on time management, from the famous ‘Getting Things Done’ to less famous works like ‘How to Live on 24 hours a day’ or ‘How to get everything done and still have time to play’. These books may have value, as they represent the struggles and experiments of real people to get grips on their life. Still, it may also be worthwhile to look at people who achieve what time-managers strive to obtain, which is not so much cramming as much stuff as possible in one’s daily allotment of 24 hours, but a successful life.

If you ask people why they cannot achieve their goals, the likely answer is “because I don’t have enough time’. Or perhaps more worryingly, even many people without grand (or not so grand) goals seem to be suffering from chronic stress, which, even if it does not lead to burnout, likely leads to a lower life expectancy. Scientists in academia are no exception to the ‘rat race’ of modern life, they even likely work longer hours than the average person, somewhere in the neighbourhood of 55 to 61 hours a week.

Now, this may be logical; after all, prizes, grants and careers are typically awarded to scientists who produce quite a lot of work. And it stands to reason that if you work longer hours, you can produce more work. However, if you look to research that tried to predict the success of a number of scientists, there does not seem to be a relationship between numbers of hours worked in the week and scientific accomplishment; in fact, most top scientists described themselves as ‘lazy’. What is going on?

The first explanation, that top scientists have much better brains and therefore can work faster, does not seem to hold true; all professional scientists have IQs of 120 and above, there don’t seem to be IQ differences between Nobel laureates and random scientists (as the quoted Root-Bernstein study as well as other comparative research between top and average scientists suggests).

But if raw brain power is not the issue, what is? There seem to be three factors:

1. Top scientists use their time more efficiently. This seems at least for a part because of smarter research strategies, often gleaned from their mentors (which were usually also top scientists themselves). Top scientists often do riskier, or more original, or more important, or more ‘doable’ research; they seem to spend more time finding the right question and choosing the right approach, instead of just ‘experimenting and writing.’

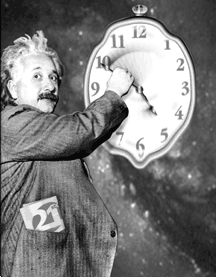

2. Next to working in smarter ways, top scientists also work with more focus, enthusiasm, and likely speed. Let’s call this ‘energy‘. Top scientists tend to be quite good at managing their energy. This happens in a quite unexpected way: they consider themselves ‘lazy’, by which it seems they mean that they only work when they feel like it, and generally don’t do things they do not like. If taken to excess, this has some disadvantages in social relationships (Einstein’s first marriage broke down because he was not a very supportive husband), but in general, being bold in doing things as much as possible only when you feel like them has some unexpected advantages. First of all, since top scientists generally do not overwork themselves (though exceptions exist) they continue finding their work joyful and interesting instead of just one more duty on the treadmill. Secondly, since they get joy out of their work itself, they can feel less attached to uncontrollable outcomes like tenure or Nobel prizes, which cause their colleagues stress and may also contribute to loss of the joy of science if the sought awards take too long coming. Thirdly, they also have fewer ‘energy leaks’ since they do fewer things that bore or frustrate them. Fourth, by doing enjoyable things even if those are not ‘scientific’, such as having hobbies, like playing the piano, or sailing, or painting, they regularly recharge energy.

3. Top scientists are willing and able to spend a greater proportion of their waking time to research. Whether by character, social skills, or ambitions, top scientists tend to focus more on doing research, and less on teaching, administrative tasks, or prestigious invitations. They find it easier to say ‘no’, also to themselves! Less time spent in meetings or editing journals equals more time spent on research. Of course, it is fortunate that there are academics who are dedicated to teaching or to administration, as those are possibly even more needed than ‘pure research-heads’. And some people simply love teaching or getting a high-status administrative position. Still, top scientists found it easier to focus on research, the Root-Bernstein paper reported that they much more rarely took up administrative tasks than average scientists, and if they did, they tried to drop them as quickly as possible. So next to a generally more productive research strategy (point 1), top scientists tend to have certain interests and priorities which differ from the average (less aiming for status and social contacts, more aiming for research) and are skilled enough to get away with it.

These factors led to the surprising interview results of Root-Bernstein that while average scientists wished they had more hours in their day, top scientists considered themselves to have plenty of time. They had fun, and they were paid for it!

If one would compare it to time management books, great scientists could be considered (in the ‘getting things done’-parlance) to drop almost everything, leading to very small ‘to-do’-lists. And since they mostly did what they enjoyed, problems with procrastination (like discussed in ‘How to get everything done and still have time to play’) also largely disappeared (largely, not entirely, the later Nobel prize winner Murray Gell-Mann had a huge writer’s block, not only as a student, but even when he was a famous, Nobel prize winning physicist, though that of course involved writing, not research).

The most interesting question may however be: how can we apply this knowledge to our own lives?

First, try to find effective strategies. The first obvious approach is try to befriend people who are successful in your field (or at least more successful than you) and talk with them, try find out how they approach problems or tasks. That may take care of the ‘effective strategy’-part. Of course, you can also experiment with approaches and see what works for you (as most self-help-book authors do), but finding a role model may save you lots of trial-and-error.

Secondly, try to enjoy your life more. Which for a part may depend on getting comfortable with wanting less, not being a person who wants a career and a relationship and a busy social life and lots of travel and a gloriously large and clean house and who knows what else (like kind of everything your friends have on Facebook). Of course, this is easier said than done. Not only is it scary (though for that it can help to know that other research kind of confirms Root-Bernstein’s finding: also outside science, happiness leads to success, so don’t fear too much that your success will be sacrificed on the altar of happiness), but it is also hard. It is not that easy to be happy. There are gratitude exercises, kindness exercises, but I guess the great scientists generally did not do such exercises but consciously or unconsciously maintained three principles: do what you like, do what you value, and let go of whether you achieve a certain goal or not.

The third item – spending more time on activities that are relevant to success in the direction you want to go- can also be complicated. If you like the other activities more than research, it seems legitimate to spend more time on them, though you should not complain then that scientific success eludes you. But do be honest with yourself: are you doing all those other activities for fear of being disliked or fired? Or do you do them because you burned yourself out on research by working too hard on projects that did not inspire you? In the first case, you may need to work on your skills, network, self-confidence or simply move to a less-demanding career. If the second, try to enjoy your research as per the second of three rules.

So be smart, be effective, and have fun too! And till next time!